Add your promotional text...

Grotesque, A Gothic Epic: Comparison And Contrast Against Select Gothic Works (Research Provided by Grok AI 2025)

Grotesque, A Gothic Epic by G.E. Graven (published online since 1998) is a self-described historical epic adventure that aligns closely with the gothic genre's core conventions, while emphasizing its titular "grotesque" element through monstrous hybridity, supernatural horror, and themes of faith amid apocalyptic peril.

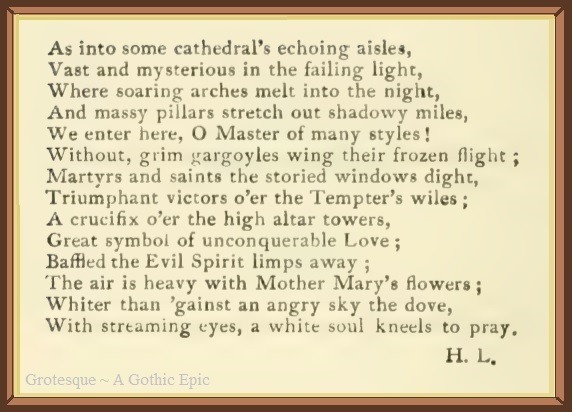

Classic Gothic Tropes

The gothic genre, originating in the 18th century with works like Horace Walpole's The Castle of Otranto, typically features medieval or pseudo-medieval settings, isolated protagonists facing persecution, supernatural intrusions into the rational world, decaying institutions (e.g., abbeys, castles), religious tension, and an atmosphere of dread and the sublime.

Medieval Setting and Architecture: Set in the Late Middle Ages (1331–1352 A.D.), the novel evokes gothic atmosphere through castles, monasteries, kings, popes, and ecclesiastical structures—hallmarks of the genre's fascination with the oppressive weight of historical and religious institutions.

Supernatural and Demonic Elements: Fallen angels attempting to escape Hell, spirits, demons, and the looming threat of a medieval Armageddon introduce the genre's characteristic blend of the marvelous and the terrifying, reminiscent of biblical-apocryphal horrors in works like Milton's Paradise Lost (a frequent gothic influence) or Matthew Lewis's The Monk.

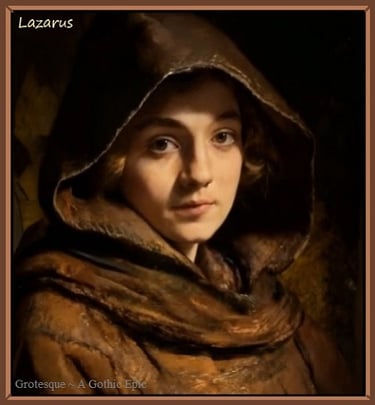

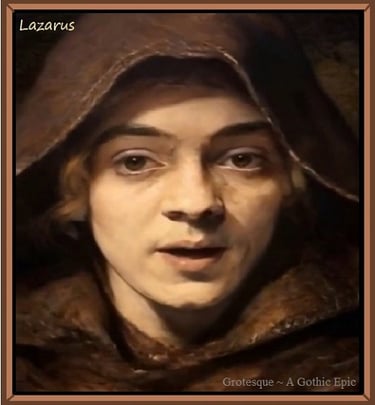

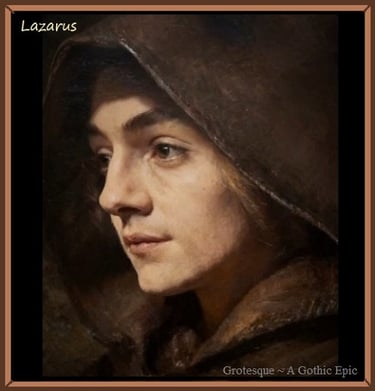

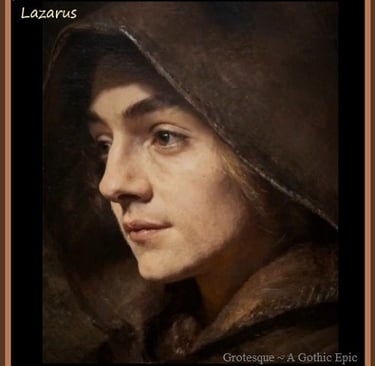

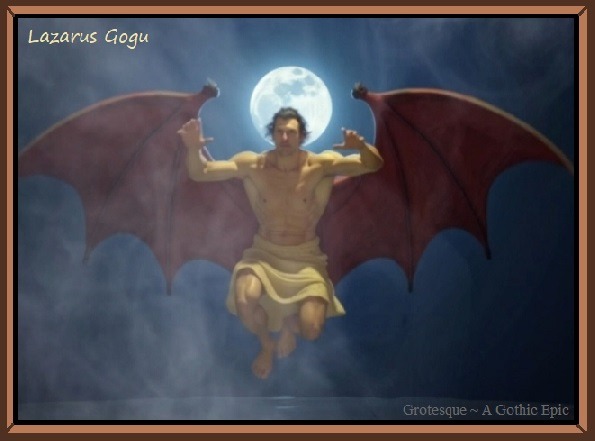

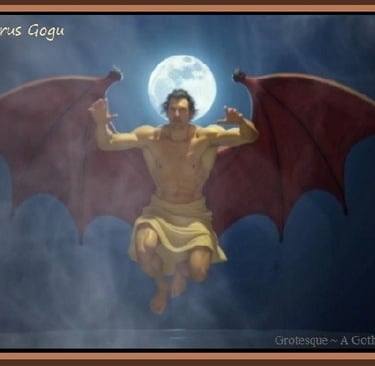

Persecuted Protagonist: The hero, Lazarus Gogu—an abbey squire who is also a winged grotesque—is hunted by a hostile world of pious yet fanatical humans who seek to destroy him. This mirrors the isolated, misunderstood outcasts in classics like Mary Shelley's Frankenstein or Victor Hugo's The Hunchback of Notre-Dame.

Emphasis on the Grotesque

The novel's title and protagonist directly engage the grotesque, a key subset of gothic aesthetics involving distorted, hybrid forms that evoke both fascination and revulsion (often linked to architectural gargoyles/chimeras). Lazarus's winged form embodies this: a human-angelic hybrid evoking biblical Nephilim (drawn from sources like the Book of Enoch and Genesis 6:2), blending beauty, monstrosity, and divine curse.

Themes of Faith, Redemption, and Apocalypse

Themes of undying love, ultimate redemption, and maintaining faith amid impossible evil align with gothic explorations of morality, sin, and the sublime terror of the divine/demonic. The apocalyptic stakes elevate it to an epic scale, blending traditional gothic introspection with grand, Miltonic cosmic conflict.

As a fully illustrated online work dedicated to Edgar Allan Poe, it positions itself explicitly within the gothic tradition, extending 19th-century romantic gothic into a modern, multimedia form while rooting its mythology in ancient texts for an aura of forbidden knowledge—a classic gothic device. Overall, it fits as a neo-gothic revival piece, amplifying the genre's medieval supernaturalism and grotesquerie into an epic narrative of survival and cosmic redemption.

Tone And Style Demonstrated by Graven

In Grotesque, A Gothic Epic by G.E. Graven, the tone is predominantly dark, ominous, and melancholic, infused with a profound sense of dread, persecution, and cosmic horror. This aligns deeply with traditional gothic conventions, evoking the oppressive atmosphere of inevitable doom found in works by Edgar Allan Poe (to whom the novel is dedicated) or Matthew Lewis. The narrative sustains a pervasive feeling of isolation and existential threat: the protagonist, Lazarus Gogu—a winged hybrid creature—is relentlessly hunted by a fanatical human world while navigating threats from demonic forces seeking apocalyptic escape. This creates a tone of unrelenting tension, blending terror with poignant sorrow, as themes of undying love, fractured faith, and redemption struggle against overwhelming evil.

Graven balances this darkness with moments of sublime beauty and tragic pathos, particularly in depictions of Lazarus's inner world—his hybrid nature evokes both revulsion and empathy, much like the creature in Frankenstein. The apocalyptic stakes amplify the tone to epic proportions, shifting from intimate gothic introspection to Miltonic grandeur, where personal suffering mirrors a broader battle between divine order and infernal chaos.

Stylistically, the prose is ornate and descriptive, favoring rich, atmospheric language to immerse readers in the medieval setting of castles, monasteries, and plague-ravaged landscapes (1331–1352 A.D.). Graven employs elevated, poetic diction reminiscent of 19th-century romantic gothic writers, with detailed sensory descriptions of the grotesque body (Lazarus's wings and form draw from biblical Nephilim lore) and supernatural intrusions. This creates a heightened, almost lyrical quality that contrasts the horror, emphasizing the sublime terror of the divine and demonic.

The novel's fully illustrated format further enhances the style: Graven's own artwork integrates visual grotesquerie—distorted figures, gargoyle-like hybrids, and shadowy ecclesiastical scenes—directly into the text, making it a multimedia experience that amplifies the tonal dread through graphic reinforcement. Overall, the style is deliberate and immersive, prioritizing emotional intensity and forbidden mythic depth over minimalist realism, resulting in a neo-gothic revival that feels both archaic and intensely personal.

Style Comparison: Graven And Poe

G.E. Graven's Grotesque, A Gothic Epic explicitly pays homage to Edgar Allan Poe—the novel and its hosting site are dedicated to him—sharing several core elements of Poe's gothic style while diverging in scale, structure, and medium.

Shared Elements

Tone of Melancholy, Dread, and the Macabre: Both evoke a pervasive atmosphere of despair, isolation, and psychological torment. Poe's tales, such as "The Fall of the House of Usher" or "Ligeia," infuse settings and characters with melancholy and impending doom, often tied to loss, madness, or the supernatural. Similarly, Graven sustains an ominous, sorrowful tone through Lazarus Gogu's persecution as a monstrous outcast, blending personal anguish with cosmic horror from demonic threats and apocalyptic stakes.

The Grotesque and Supernatural: Poe masterfully employs the grotesque—distorted minds, decaying bodies, and bizarre events—to explore the boundaries of beauty and terror (e.g., premature burial in "The Premature Burial" or hybrid obsession in "Ligeia"). Graven amplifies this with literal grotesquerie: the protagonist's winged, gargoyle-like form draws from biblical hybrids, evoking revulsion and fascination akin to Poe's symbolic distortions.

Ornate, Atmospheric Prose: Poe's style features rhythmic, sumptuous language with rich sensory details, symbolism, and a sense of the sublime to heighten emotional intensity. Graven mirrors this in elevated, poetic diction and vivid descriptions of medieval decay, monasteries, and demonic intrusions, creating an immersive dread.

Key Differences

Scale and Structure: Poe excels in concise short forms, building to a unified "single effect" of terror or revelation through tight plotting and psychological introspection. Graven's work is an expansive epic novel—an illustrated online saga spanning historical events, battles, and redemption arcs—shifting toward Miltonic grandeur rather than Poe's compressed intensity.

Medium and Visual Integration: Poe relies purely on textual evocation, with illustrations coming later from adapters. Graven's novel is fully illustrated by the author, integrating gothic artwork directly into the narrative for a multimedia experience that visually reinforces the grotesque, extending Poe's influence into a modern, graphic form.

Psychological vs. Epic Focus: Poe delves deeply into individual psyche—madness, guilt, and subconscious horror—often with unreliable narrators. Graven emphasizes external action, faith amid persecution, and apocalyptic adventure, with less emphasis on interior monologue and more on heroic survival.

Overall, Graven channels Poe's mastery of gothic atmosphere and grotesquerie as a foundational influence, adapting it into a broader, visually enhanced epic that reveres Poe while expanding the genre's scope.

Influence of Mary Shelly

In Grotesque, A Gothic Epic by G.E. Graven, the influence of Mary Shelley—particularly her seminal 1818 novel Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus—is evident through thematic parallels, character archetypes, and explorations of the grotesque, though the work lacks explicit dedication or direct references to her (unlike its overt homage to Edgar Allan Poe).

The Persecuted Monstrous Outcast

Shelley's most enduring contribution to the gothic genre is the sympathetic monster: a being artificially created or born different, physically grotesque, intellectually capable, and yearning for acceptance, yet rejected and hunted by a fearful society. This evokes profound pathos and critiques human prejudice.

Lazarus Gogu, the winged protagonist (a human-angelic hybrid inspired by biblical Nephilim), mirrors Shelley's Creature: both are hybrid forms blending beauty and horror, evoking simultaneous fascination and revulsion.

Like the Creature, Lazarus is persecuted by pious humans who view him as an abomination, forcing him into isolation while he struggles with his identity, faith, and desire for connection (including undying love).

This archetype shifts the gothic monster from pure villainy (as in earlier works) to a tragic figure eliciting empathy, a hallmark Shelley pioneered to explore abandonment, societal rejection, and the cruelty of the "normal" toward the "other."

The Grotesque Body and Hybridity

Shelley elevated the grotesque in gothic literature by making it central to themes of creation and monstrosity—her Creature's patchwork body symbolizes unnatural hubris and the sublime terror of blurred boundaries between human/divine, life/death.

Graven amplifies this with Lazarus's literal gargoyle-like wings and form, tying directly to architectural grotesques (chimeras/gargoyles) while echoing Shelley's focus on physical distortion as a source of dread and poignancy. The novel's title and visual illustrations reinforce this bodily horror, much as Shelley's vivid descriptions of the Creature's yellow eyes and translucent skin do.

Broader Thematic Echoes

Redemption and Humanity Amid Horror: Both works grapple with faith, morality, and redemption in the face of existential isolation—Shelley's Creature seeks a mate and understanding; Lazarus maintains faith amid apocalyptic evil.

Supernatural Intrusion and Cosmic Stakes: While Shelley grounds her horror in science (proto-science fiction), Graven leans biblical/demonic, but both warn of the perils of transgressing natural/divine order.

Overall, Graven's neo-gothic epic extends Shelley's legacy by adapting her empathetic monster trope into a medieval, faith-driven narrative with epic scope and multimedia visuals. This positions Grotesque within the post-Shelley gothic tradition of humanizing the grotesque to probe deeper philosophical questions about creation, prejudice, and the sublime.

Work Comparison: Graven And Stoker

While G.E. Graven's Grotesque, A Gothic Epic shows no direct influence from or reference to Bram Stoker's Dracula (1897)—unlike its explicit dedication to Edgar Allan Poe—both works engage deeply with late gothic traditions, particularly in their use of supernatural monstrosity, religious tension, and atmospheric dread.

Shared Gothic Elements

Supernatural Horror and Monstrous Figures: Stoker's Count Dracula is an aristocratic vampire invading modern England, embodying seductive evil, shape-shifting (including bat-like wings), and bloodlust as a metaphor for corruption and invasion fears.

Graven's Lazarus Gogu is a winged hybrid (Nephilim-inspired grotesque), blending angelic and demonic traits in a medieval Christian world threatened by fallen angels and apocalypse. Both monsters evoke winged, nocturnal horror, but Dracula is predatory and irredeemably evil, while Lazarus is a tragic, empathetic outcast seeking redemption.

Religious Symbolism and Good vs. Evil: Dracula pits Christian faith (crucifixes, holy wafers) against unholy vampirism, with Van Helsing leading a rational-religious crusade.

Graven amplifies biblical apocalyptic themes—demons escaping Hell, faith tested amid persecution—creating a cosmic battle where the protagonist embodies fractured divinity rather than pure antagonism.

Atmosphere of Dread and Isolation: Both sustain ominous tones through decaying settings (Transylvanian castles, foggy England in Dracula; plague-era monasteries and castles in Grotesque).

Key Differences

Narrative Structure and Style: Stoker employs an epistolary format—journals, letters, and clippings—for documentary realism and mounting suspense. Graven uses ornate, poetic prose in a linear epic saga, integrated with author's illustrations for a multimedia gothic experience.

Scope and Protagonist Role: Dracula is a Victorian invasion horror with a clear villain hunted by a group of heroes. Grotesque centers on the monster as persecuted hero in an expansive historical-apocalyptic adventure, echoing Shelley's sympathetic creature more than Stoker's predatory count.

Thematic Focus: Stoker explores fin-de-siècle anxieties (sexuality, immigration, science vs. superstition). Graven delves into ancient mythic grotesquerie, undying love, and personal redemption amid end-times peril.

In summary, both reinforce gothic conventions of the supernatural intruder and moral/religious conflict, but Graven's work inverts Stoker's monster dynamic—transforming the villainous winged predator into a sublime, redeemable grotesque—while expanding into epic, illustrated neo-gothic territory.

Work Comparison: Graven's Grotesque, A Gothic Epic and Shelley's Frankenstein

G.E. Graven's Grotesque, A Gothic Epic shares profound parallels with Mary Shelley's Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818), making it one of the clearest influences on the novel—more so than Poe's psychological intensity or Stoker's predatory horror. Both works center on a sympathetic, physically grotesque being rejected by society, using monstrosity to explore themes of creation, isolation, prejudice, and redemption.

The Sympathetic Monster Archetype

Shelley's groundbreaking innovation was humanizing the monster: an intelligent, articulate creature abandoned by its creator, yearning for companionship yet driven to violence by human cruelty. This evokes deep pathos and critiques societal fear of the "other."

Lazarus Gogu mirrors this exactly—a winged, gargoyle-like hybrid (Nephilim-inspired) who is intellectually and emotionally capable, seeking love and acceptance but hunted as an abomination by fanatical humans. Both protagonists elicit empathy through their tragic isolation and moral depth, inverting traditional gothic villainy.

The Grotesque Body and Hybridity

Both emphasize distorted physicality as a source of sublime horror and fascination. Shelley's Creature is a patchwork of reanimated parts, blurring life/death boundaries through hubris.

Graven's Lazarus embodies architectural grotesques (chimeras/gargoyles), a literal winged hybrid tying into medieval biblical forbidden knowledge. The novel's title and author's illustrations amplify this bodily dread visually, extending Shelley's textual descriptions into multimedia form.

Thematic Overlaps

Isolation and Persecution: Both beings are outcasts in hostile worlds, testing faith and humanity amid rejection.

Redemption and Morality: Themes of potential goodness corrupted by abandonment; both grapple with divine/natural order transgression.

Sublime Terror: Atmospheric dread from the unnatural intruding on the rational or sacred.

Key Differences

Origin and Scope: Shelley's horror stems from modern science and individual hubris in a framed narrative of introspection. Graven roots monstrosity in ancient biblical mythology, expanding to epic apocalyptic adventure with demonic forces and historical scale (1331–1352 A.D.).

Tone and Style: Frankenstein is elegiac and philosophical, with nested narratives. Grotesque is ornate, action-oriented, and visually integrated.

Creator Role: Victor Frankenstein abandons his creation in horror; Graven's work lacks a direct "mad scientist," focusing on divine curse and cosmic conflict.

Overall, Grotesque reveres and updates Shelley's empathetic monster trope, transplanting it into a medieval, faith-driven neo-gothic epic while preserving the core inquiry: what makes one truly monstrous—appearance, or the cruelty of those who reject it?

For further detailed analysis of Grotesque, A Gothic Epic, please refer to additional resources contained on this page.

Grotesque ~ A Gothic Epic © is legally and formally registered with the United States Copyright Office under title ©#TXu~1~008~517. All rights reserved 2026 by G. E. Graven. Website design and domain name owner: Susan Kelleher. Name not for resale or transfer. Strictly a humanitarian collaborative project. Although no profits are generated, current copyright prohibits duplication and redistribution. Grotesque, A Gothic Epic © is not public domain; however it is freely accessable through GothicNovel.Org (GNOrg). Access is granted only through this website for worldwide audience enjoyment. No rights available for publishing, distribution, AI representation, purchase, or transfer.